Microbial Prevalence and Antimicrobial Resistance in Children and Adolescents with Chronic Rhinosinusitis in South Indian Population

Received: 14-Jun-2016 / Accepted Date: 19-Jul-2016 / Published Date: 26-Jul-2016 DOI: 10.4172/2161-119X.1000248

Abstract

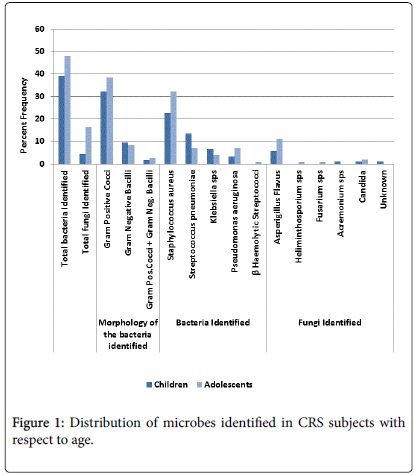

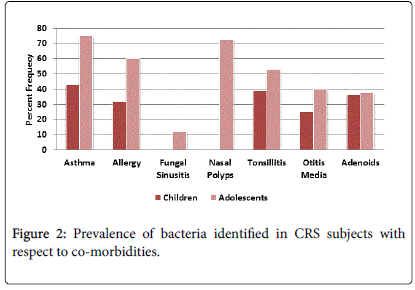

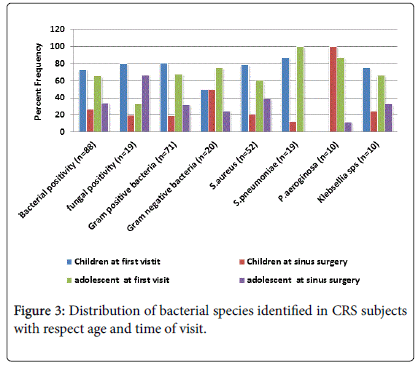

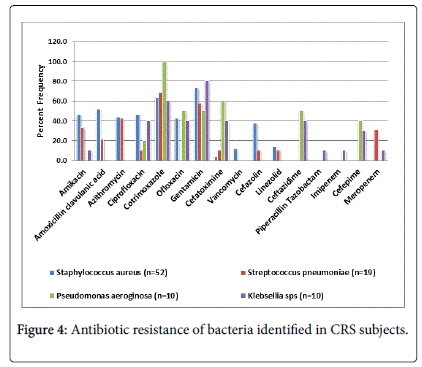

Objective: Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) is a common multifactorial upper respiratory disease with a key role of microbes in worsening of disease and its associated co-morbidities. Further, significant region specific variation in patient demographics and antibiotic resistance of causative bacteria are reported to pose difficulty in diagnosis and treatment. In India, studies on the etiology and antibiotic resistance in chronic rhinosinusitis are very meager, especially in children. The present study aimed to determine the prevalence of common causative microbes and their antibiotic resistance in children and adolescents with chronic rhinosinusitis in South Indian population. Subjects and methods: The present study was conducted on 89 children and 99 adolescents with chronic rhinosinusitis who visited MAA ENT Institute, Hyderabad, South India. The study samples were collected under the nasal endoscopic guidance from the middle meatus at first visit and sinuses at surgery. Conventional and VITEK-2 methods were used for identification and antibiotic sensitivity of the microbes. Chi-square test and multinomial logistic regression was applied to determine statistical differences between the variable using PASW v. 18.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Results: The male-female ratio was 2:1 with an average children age of 8.9 ± 3.65 years and 16.1 ± 1.23 years in adolescents. The risk for adenoids was seen in 49.2 % of children (OR; 2.6: 95% CI: 1.63-4.06) while allergic fungal sinusitis (18.1%, OR: 2.7; 95% CI: 1.12-6.57) and nasal polyps (26.6%, OR: 2.3; 95% CI: 1.07-4.86) was commonly seen in adolescents. About 26.6% of adolescents with fungal positivity also showed bacterial infection. Aspergillus flavus (68%) was the most common fungi identified. Bacterial culture rate was positive in 46.8% of the total subjects of which Streptococcus aureus was the most common bacteria (59.1%) followed by Streptococcus pnuemoniae (21.2%), Klebsiella sp. (11.4%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (11.4%) and β hemolytic streptococci (1.1%). No Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains could be identified. Streptococcus pneumonia (63.2%) was commonly identified in younger children and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (80%) was mostly seen in adolescents. The frequency of bacterial positivity in adolescents with CRS when compared to CRS children was high and varied between different associated co-morbidities. High antibiotic resistance in Staphylococcus aureus was seen towards gentamicin (73%) and co-trimoxazole (64%), Streptococcus pnuemoniae to gentamicin (58%), cotrimoxazole (68%) and meropenem (32%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa to co-trimoxazole (100%), cefatoximine (60%) and cefatazidime (50%) while Klebsiella sp. to gentamicin (80%) and co-trimoxazole (60%). Streptococcus aureus showed high sensitivity to cefatoximine (95.8%) and Streptococcus pnuemoniae for ofloxacin (100%), ciprofloxacin (89.5%) and cefazolin (89.5%). Pseudomonas aeruginosa showed high sensitivity for amikacin (100%) and ciprofloxacin (80%) and Klebsiella sp. for amikacin (100%) Conclusion: Significant regional specific variation in bacterial etiology that differed with age, severity and comorbidities was observed in children and adolescents with chronic rhinosinusitis. High antimicrobial resistance in the cultures of chronic rhinosinusitis patients at their first visit and also at sinus surgery warrants urgent need for early initiation of personalized interventions for better management of the infectious disease.

Keywords: Chronic rhinosinusitis; Allergic fungal sinusitis; Nasal polyps; Adenoids; Antibiotic sensitivity; Functional endoscopic sinus surgery; Chronic suppurative otitis media

252215Introduction

Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) is a common multifactorial inflammatory disorder of the upper airway system that drastically affects the patient’s quality of life across all ages and socioeconomic conditions of millions of people worldwide [1]. About 5-15% of the worldwide population is affected with chronic rhinosinusitis yet paucity of data exists in relation to etiopathogenesis, especially in children [2]. Various demographic and socioeconomic factors are reported to cause differences in CRS manifestation which affects management and recurrence rate of the disease [3,4]. Clinicopathophysiological mechanisms such as immaturity of the immune system, smaller ostia of the sinuses, increased respiratory tract infections and adenoidal hypertrophy in children while tissue remodeling and greater irreversible scarring due to inflammation in adults contribute to the disease worsening in chronic rhinosinusitis [5]. Further, presence of nasal pathogens leads to longer mean duration of symptoms and greater severity of the inflammation [6]. The role of bacteria differed with respect to different chronic rhinosinusitis comorbidities which further increase variation in disease management in children as well as in adults [7,8].

Sinusitis and its associated complications are more frequently treated with antibiotics to prevent the onset of complications and the need for surgical interventions [9]. Antibiotic treatment can promote subsequent growth of various bacteria, often to new multidrug resistant strains, on the mucosal epithelium with frequencies and changes that may vary with the use of different antibiotics, between age groups and clinical entities [10,11]. Misdiagnosis of the symptoms in many cases with upper respiratory tract infections, indiscriminate prescribing of antibiotics by general practitioners including broadspectrum antibiotics, and ease of obtaining antibiotics has promoted the microbial resistance for many antibiotics [12,13]. The susceptibility trends among common pathogens appear to have stabilized over the past years as measures have been taken up in many countries but high prevalence of multidrug resistance remains as a major concern [13,14]. Also, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently estimated that antimicrobials usually prescribed often to treat acute respiratory tract infections in children and adults are still at inappropriately high rates. Continuing research is therefore needed to refine physician awareness and to evaluate regional differences in antibiotic resistance that may result in variations with significant effects upon disease progression and management.

In India, very meager studies are been reported on etiology of chronic rhinosinusitis, especially in children. The choice of antibiotics is discretionary and usually not made based on microbial culture and sensitivity results which promotes the high risk for bacterial resistance. Misconceptions exist about the use and indications of antibiotics and lack of knowledge regarding antibiotic resistance is prevalent in India [15]. The purpose of this study was to determine the etiology, and the prevalence of major bacterial and fungal pathogens and antibiotic resistance of the identified bacteria in children and adolescents of South Indian population.

Study, Subjects and Methods

188 CRS subjects including 89 children and 99 adolescents who underwent treatment at MAA ENT Hospitals, Hyderabad were considered for the study. Clinical diagnosis was based upon presence of two or more symptoms of nasal obstruction, nasal congestion, anterior nasal discharge, posterior nasal drip, facial pain, cough; atleast one of the endoscopic signs of nasal polyps, mucosal obstruction and/or mucopurulent discharge mainly from middle meatus, oedema and mucosal changes within the ostiomeatal complex and/or sinuses as seen through computed tomography. The criteria for the diagnosis of nasal allergy were mainly by the symptoms such as nasal discharge, nasal itching and sneezing for more than 5 times a day. Diagnosis of adenoids was made when greater than 50% of nasopharyngeal space occupied by soft tissue in the X-ray neck lateral view. The confirmation of diagnosis was by X-ray in subjects less than 13 yrs and computed tomography scan in subjects more than 13 yrs. Subjects who have not been on antibiotic therapy during the first visit and who have stopped their antibiotic use for atleast 3 weeks before surgery were included in the study. CRS subjects with immune compromised conditions, cystic fibrosis and nasocominal infections were excluded. The study samples were collected in the first visit if purulent discharge was present in the middle meatus and in patients when discharge was not seen in the middle meatus due to blockage of sinus opening the samples were collected at the surgery under the nasal endoscopic guidance. Surgical interventions were done when the condition could not be managed by the therapeutic interventions. Identification and antibiotic sensitivity of the microbes were performed by the conventional and VITEK-2 method. Data related to detailed medical history, clinical findings and the findings of endoscopic examination, computed tomography scanning and microbiological assessments were recorded and the data obtained was analyzed using PASW ver. 18.0 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, US). Continuous data was presented as means and standard deviations. Chi-square test and multinomial logistic regression was used to determine statistical differences between the age, sex, co-morbidities, type of microbial pathogen and their antibiotic sensitivity and resistance. The study was performed after approval of the institutional research ethics committee for biomedical research.

Results

The mean age of children was 8.9 ± 3.65 years and 16.1 ± 1.23 years in adolescents. Male preponderance of 2:1 was noticed in both children and adolescents. 51.6% of the CRS children with adenoids were affected with allergic rhinitis, 32.2 % cases with CSOM and 16.6% cases with asthma. Allergic fungal sinusitis (AFS) was commonly found in adolescents (18.1%) of which 57.1% of cases had nasal polyposis while 19.9% had asthma. Allergic Rhinitis was the most common comorbidity in both the age groups. Allergic rhinitis with nasal polyps was present in 21.2% of CRS subjects and 4.2% of CRS subjects had allergic rhinitis with nasal polyps and asthma. Of the total subjects, 36.7% of cases underwent primary and 10.1% of cases had revised functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS). The distribution of risk factors and co-morbidities of CRS in children and adolescents is given in Table 1.

| Characteristic | Total | Children | Adolescents | p-value | Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 188 | 89 (47.3) | 99 (52.7) | ||

| Male | 130 (69.1) | 61 (68.5) | 69 (69.7) | 0.876 | 1.056 (0.568-1.962) |

| Female | 58 (30.9) | 28 (31.5) | 30 (30.3) | ||

| Risk Factors/Co-morbidities | |||||

| Adenoids | 63 (33.5) | 44 (49.4) | 19 (19.2) | <0.001 | 2.6 (1.63-4.06) |

| Allergic rhinitis | 102 (54.2) | 43 (48.3) | 59 (59.6) | 0.143 | 0.81 (0.62-1.06) |

| Fungal Sinusitis | 26 (13.8) | 8 (9) | 18 (18.1) | 0.035 | 2.7 (1.12-6.57) |

| Nasal Polyps | 38 (20.2) | 12 (13.5) | 26 (26.3) | 0.045 | 2.3 (1.07-4.86) |

| Tonsillitis | 78 (41.5) | 38 (42.7) | 40 (40.4) | 0.769 | 1.06 (0.75-1.48) |

| Otitis Media | 79 (42.0) | 32 (36) | 47 (47) | 0.139 | 0.75 (0.54-1.07) |

| Asthma | 23 (12.2) | 14 (15.7) | 9 (9.1) | 0.186 | 1.73 (0.79-3.80) |

| History of sinus surgery | |||||

| No Surgery required | 100 (53.2) | 48 (53.9) | 52 (52.5) | 0.615 | ref a |

| Sinus Surgery | 69 (36.7) | 34 (38.2) | 35 (35.4) | 0.87 | 0.950 (0.514 - 1.755) |

| Sinus Surgery Revision | 19 (10.1) | 7 (7.9) | 12 (12.1) | 0.374 | 1.582 (0.576 - 4.351) |

Table 1: Demographic and clinical characteristics of children and adolescents with chronic rhinosinusitis (N=188), a p-value significance is based on multinomial logistic regression (2-sided), p-value significance is based on Fisher's Exact Test (2-sided), Odds ratio computed based on chi-square test.

A total of 88 bacterial isolates were recovered of which 94.3% were positive for single culture and 5.7% had multiple cultures. 80.6% of the cultures were Gram-positive cocci, 22.7% gram-negative rods and 5.6% were mixed cultures of gram positive cocci and gram negative rods. Co-infection of bacteria and fungus was noted in 4.4% of adolescents. S.aureus was the most frequently cultured organism (59.9%), followed by S. pneumonia (21.5%), P. aeruginosa (11.4%), Klebsiella sp. (11.4%) while no methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains could be identified. Klebsellia sp. was identified more frequently (60%) in polymicrobial infections. Aspergillus flavus was the most common fungi identified. Staphylococcus aureus was the most common pathogen in both the age groups, Staphylococcus aureus was seen in 59% was commonly identified in younger children and Pseudomonas aeruginosa was mostly seen in adolescents at their first visit. The distribution of microbes with respect to age in CRS subjects is given in Figure 1. The prevalence of bacteria with respect age and severity is given in Figure 2.

Bacterial culture rate was positive in 46% of the total subjects and varied with comorbidities, 44.7% of cases presented with allergy, 47.1% with nasal polyps, 54.5% asthma, 30.4% otitis media, 36.7% adenoids, 42.9% tonsillitis subjects. 57% of allergic fungal sinusitis subjects had nasal polyps. The bacterial prevalence in CRS subjects with regard to comorbidities and age is given in Figure 3. In CRS children with adenoids the microbial culture rate was 35.5% of which S. aureus was present in 72.7% of cases and S. pneumonia was seen in 18.1% of cases. In subjects with CSOM, bacterial positivity was found in 29.7% of the cultures of which S. aureus was 45.4% and Streptococcus pneumonia was identified in 36.3% cases. Staphylococcus aureus was seen in 59% of bacterial positive cases in CRS subjects with allergic rhinitis. About 77% of isolates from adolescents with nasal polyps showed bacterial positivity. The prevalence of gram positive bacteria also differed with co morbidities, S. aureus was seen in 72.7% and S. pneumonia was seen 18.1% in CRS subjects with adenoids while in case of CRS subjects with CSOM, S. aureus was identified in 45.4% and Streptococcus pneumonia in 36.3% cases.

Antibiotic resistance was observed in all the gram positive and gram negative bacterial isolates which differed with comorbidities and severity of the disease (Figure 4). High antibiotic sensitivity of Staphylococcus aureus was seen against cefatoximine (95.8%), Streptococcus pnuemoniae for ofloxacin (100%), cefazolin (89.5%), and cefatoximine (89.5%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa for amikacin (100%) and ciprofloxacin (80%) and Klebsiella pnuemoniae for amikacin (80%). All the Staphylococcus aureus isolates obtained at revision surgery were resistant to cotrimoxazole, 75% to amoxicillin clavunate and 50% to gentamicin. However, no difference in the antibiotic sensitivity was observed between the children and adolescents.

Discussion

Chronic Rhinosinusitis (CRS) is the common upper respiratory disorder but continues to remain as a neglected disorder, especially in developing countries [16]. Bacterial infection plays a key role in worsening of CRS that can lead to asthma exacerbation, otitis media, recurrent polyps and refractory symptoms during post-sinus surgery [17]. The predominance of aerobic and anaerobic organisms cultured in children was reported to be different from adults and also with reference to site of isolation [18]. In the present study, identical potential pathogens were noticed in middle meatus and sinus aspirates which is in agreement with the earlier reports [19-21].

In a recent metanalysis study by Thanasumpun et al. [22] conducted on endoscopically derived bacterial cultures of adults with chronic rhinosinusitis reported Coagulase Negative Staphylococcus followed by Staphylococcus aureus , Haemophilus influenza and Pseudomonas aeruginosa to be the most common aerobes and Peptostreptococcus species and bacteroides species as the common anaerobes [22]. In pediatric chronic rhinosinusitis, polymicrobial infections and positive cultures of three major bacteria: Haemophilus influenzae (37.3%), Streptococcus pneumoniae (28.4%) and Moraxella catarrhalis (11.8%) were in Taiwan population whereas in chronic rhinosinusitis children of German population Streptococcus pneumoniae (33%) was the predominant followed by Haemophilus influenzae (27%), Staphylococcus aureus (13%), Moraxella catarrhalis (11%) and Streptococci (7%) [23,24]. In children of Chinese population both alpha-hemolytic Streptococcus (20.8%) and Haemophilus influenzae (19.5%) predominated followed by Streptococcus pneumoniae (14.0%), Coagulase-Negative Staphylococcus (13.0%), Staphylococcus aureus (9.3%) and anaerobes (8.0%) [25]. Unlike the above reported studies, the present study identifies Staphylococcus aureus (35%) to be the most common pathogen in both the age groups while other bacteria identified were S. pneumonia (22.3%) and P. aeruginosa (9%) showing variation with respect to severity and age of the chronic rhinosinusitis subjects. 64.7% subjects undergoing sinus surgery were positive for S. aureus . Polymicrobial infection was seen in only in 2.7% of study subjects. Also, no anaerobes were identified in children and adolescents with CRS which is not in agreement with the study conducted by Slack et al. [26].

Methicillin-resistance Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is known to be a common causative pathogen for chronic rhinosinusitis with greater recurrence rate and high prevalence and rising incidence in almost all countries [27]. According to a meta analysis study conducted by Macoul et al. the prevalence of MRSA was 1.8%-20.7% for CRS subjects [28]. The present study could not identify any MRSA strains and other predominant bacteria as reported in other studies in chronic rhinosinusitis children and adolescents. Also, a study from Karnataka, South India, reported only 3% of MRSA strains in CRS which indicates lesser burden of MRSA in community acquired infectious diseases in South Indian population [29].

Nasopharyngeal carriage of the S. pneumoniae was associated with younger age and considered to protect against colonisation by major pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus and Haemophilus influenzae and thereby reducing their likelihood of causing invasive disease [30]. Reduction of pneumococcal carriage in children and increase in the incidence of S. aureus related infections was also attributed due to immunization with pneumococcal conjugate vaccine [31]. The present study finds Streptococcus aureus in 42.6% of bacterial isolates identified from younger children and 55.7% of subjects, who underwent sinus surgery, thereby supports the study conducted by Shaikh et al. [32].

Multiple co-morbidities like adenoids, otitis media, allergic rhinitis, asthma and nasal polyps are associated with chronic rhinosinusitis [1]. Significant correlation was seen between bacterial isolation rate of adenoid cultures to sinusitis grade and chronic suppurative otitis media [33,34]. Pathogens isolated from adenoids were also resistant to antibiotics that allowed infection to persist with an increased incidence of acute and unresolved otitis media [35]. Recent evidence suggests that the degree of atopy, is not associated with progression to chronic rhinosinusitis in pediatric age group but asthma is significantly associated which suggests a link between upper and lower airways and independent of allergic etiology [36]. In the present study, the prevalence of adenoids was more common in CRS children while nasal polyps were more commonly seen in CRS adolescents. Allergic rhinitis was the predominant comorbidity seen in children as well as in adolescents. Further, an association higher rate of Staphylococcus aureus was seen with allergic rhinitis as reported by Refaat et al. [37]. A significant correlation between allergy, asthma, rhinosinusitis and high positive rate of bacteria was also observed which is in accordance with earlier reports [38-40]. Increase in bacterial positivity in allergic rhinitis subjects with nasal polyps and asthma was found which is similar to the observation made by Ramakrishna et al. [41]. A very high frequency of bacterial positivity was noticed in CRS adolescents with nasal polyps. However, the study could not identify any microbes in the isolates from CRS children with nasal polyps.

With regard to allergic fungal sinusitis (AFS), Ferguson et al, noted a geographical variability in the incidence of AFS and fungal species associated with the disease process. In the Southern United States, dermatiaceous fungi are the most common when compared with the Northern United States, while Aspergillus species was the cause in most cases reported in the Middle East [42]. However, none of the allergic fungal sinusitis case was noticed in the northwest of Turkey [43]. In the present study, prevalence of 13.8% of allergic fungal sinusitis was noted in the study subjects and was more commonly seen in adolescents (68%). Asperigillus flavus being the most common fungi noted in both the age groups. Incidence of fungal sinusitis with nasal polyposis was reported to be 7% by Braun et al. [44]. Telmesani [45] reported allergic fungal sinusitis with nasal polyposis as 12.1% and with asthma as 30% to 40% [45]. In the present study, a very high prevalence of 57.1% of allergic fungal sinusitis with nasal polyposis was observed. Asthma was observed in 19.9% of allergic fungal sinusitis subjects.

Different survival strategies and mechanisms are adopted by the pathogens causing difficulty in management of severe infections [11]. Increase in evolution of antibiotic resistance usually to multiple drugs in almost all bacterial pathogens has enhanced the chances of survival and extension into the community [11,46]. Since the present study has observed ethnic variation in the prevalence of microbes and antibiotic resistance in isolates of both the age groups it signifies the importance of microbial evaluation before initiations of any therapeutic interventions.

Conclusion

To our knowledge this is the first study to report etiology and antibacterial resistance in chronic rhinosinusitis children and adolescents in Indian population. The bacterial and fungal prevalence varied with respect to age, severity and co-morbiditites. High rate of antibiotic resistance in all the microbial isolates, Staphylococcus aureus , Streptococcus pnuemoniae , Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Klebsiella pneumoniae warrants utmost need for early initiation of personalized interventions and management measures in chronic rhinosinusitis children and adolescents.

Acknowledgement

I thank ICMR for supporting me in the form of SRF grant. I would also like to thank Ms. B. Sunita G Kumar, CMD, MAA ENT Hospitals for her support and cooperation in carrying out the work. I thank all my labmates, JV Ramakrishna, D Dinesh and P Padmavathi for helping me to carry out this work.

References

- Smith WM, Davidson TM, Murphy C (2009) Regional variations in chronic rhinosinusitis, 2003-2006.Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 141: 347-352.

- Sacre-Hazouri JA1 (2012) [Chronic rhinosinusitis in children].Rev AlergMex 59: 16-24.

- Kristo A, Uhari M, Kontiokari T, Glumoff V, Kaijalainen T, et al. (2006) Nasal middle meatal specimen bacteriology as a predictor of the course of acute respiratory infection in children.Pediatr Infect Dis J 25: 108-112.

- Scheid DC, Hamm RM (2004) Acute bacterial rhinosinusitis in adults: part I. Evaluation.Am Fam Physician 70: 1685-1692.

- Beule A (2015) Epidemiology of chronic rhinosinusitis, selected risk factors, comorbidities, and economic burden.GMS Curr Top Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg 14: Doc11.

- Kenealy T, Arroll B (2013) Antibiotics for the common cold and acute purulent rhinitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 6:CD000247.

- Slack CL, Dahn KA, Abzug MJ, Chan KH (2001) Antibiotic-resistant bacteria in pediatric chronic sinusitis. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 20: 247–250.

- Davies J, Davies D (2010) Origins and evolution of antibiotic resistance.MicrobiolMolBiol Rev 74: 417-433.

- Llor C, Bjerrum L (2014) Antimicrobial resistance: risk associated with antibiotic overuse and initiatives to reduce the problem.TherAdv Drug Saf 5: 229-241.

- Sahm DF, Brown NP, Thornsberry C, Jones ME (2008) Antimicrobial susceptibility profiles among common respiratory tract pathogens: A Global perspective. Postgrad Med 120:16-24.

- Harris AM, Hicks LA, Qaseem A (2016) Appropriate Antibiotic Use for Acute Respiratory Tract Infection in Adults: Advice for High-Value Care From the American College of Physicians and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ann Intern Med 164: 425-434.

- Agarwal S, Yewale VN, Dharmapalan D (2015) Antibiotics Use and Misuse in Children: A Knowledge, Attitude and Practice Survey of Parents in India.J ClinDiagn Res 9: SC21-24.

- Wu AW, Shapiro NL, Bhattacharyya N (2009) Chronic rhinosinusitis in children: what are the treatment options?Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 29: 705-717.

- Leiberman A, Dagan R, Leibovitz E, Yagupsky P, Fliss DM (1999) The bacteriology of the nasopharynx in childhood.Int J PediatrOtorhinolaryngol 49 Suppl 1: S151-153.

- Bernstein JM, Dryja D, Murphy TF (2001) Molecular typing of paired bacterial isolates from the adenoid and lateral wall of the nose in children undergoing adenoidectomy: implications in acute rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 125: 593-7.

- Uhliarova B, Karnisova R, Svec M, Calkovska A (2014) Correlation between culture-identified bacteria in the middle nasal meatus and CT score in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. J Med Microbiol63 :28-33.

- Ramakrishnan VR, Feazel LM, Abrass LJ, Frank DN (2013) Prevalence and abundance of Staphylococcus aureus in the middle meatus of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis, nasal polyps, and asthma. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 4: 267-271.

- Corriveau MN, Zhang N, Holtappels G, Van Roy N, Bachert C (2009) Detection of Staphylococcus aureus in nasal tissue with peptide nucleic acid-fluorescence in situ hybridization.Am J Rhinol Allergy 23: 461-465.

- Thanasumpun T, Batra PS (2015) Endoscopically-derived bacterial cultures in chronic rhinosinusitis: A systematic review.Am J Otolaryngol 36: 686-691.

- Huang WH, Fang SY (2004) High prevalence of antibiotic resistance in isolates from the middle meatus of children and adults with acute rhinosinusitis.Am J Rhinol 18: 387-391.

- Fickweiler U, Fickweiler K (2005) [The pathogen spectrum of acute bacterial rhinitis/sinusitis and antibiotic resistance].HNO 53: 735-740.

- Hsin CH, Su MC, Tsao CH, Chuang CY, Liu CM (2008) Bacteriology and antimicrobial susceptibility of pediatric chronic rhinosinusitis: a 6-year result of maxillary sinus punctures. Am J Otolaryngol 31:145-9.

- Slack CL, Dahn KA, Abzug MJ, Chan KH (2001) Antibiotic-resistant bacteria in pediatric chronic sinusitis.Pediatr Infect Dis J 20: 247-250.

- Penttilä M, Savolainen S, Kiukaanniemi H, Forsblom B, Jousimies-Somer H (1997) Bacterial findings in acute maxillary sinusitis--European study.ActaOtolaryngolSuppl 529: 165-168.

- Rujanavej V, Soudry E, Banaei N, Baron EJ, Hwang PH, et al. (2013) Trends in incidence and susceptibility among methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from intranasal cultures associated with rhinosinusitis. American Journal of Rhinology & Allergy 27: 134–137.

- Panduranga KM, Vijendra SS , Nithin M, Nitish S (2013) Microbiological analysis of paranasal sinuses in chronic sinusitis - A South Indian coastal study Egyptian Journal of Ear, Nose, Throat and Allied Sciences 14: 185-189.

- Charalambous BM (2007) Streptococcus pneumoniae: pathogen or protector? Reviews in Medical Microbiology 18: 73-78.

- Olarte L, Hulten KG, Lamberth L, Mason EO, Kaplan SL (2014) Impact of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on chronic sinusitis associated with Streptococcus pneumoniae in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 33:1033-6.

- Shaikh N, Wald ER, Jeong JH, Kurs-Lasky M, Bowen A, et al. (2014) Predicting response to antimicrobial therapy in children with acute sinusitis.J Pediatr 164: 536-541.

- Shin KS, Cho SH, Kim KR, Tae K, Lee SH, et al. (2008) The role of adenoids in pediatricrhinosinusitis.Int J PediatrOtorhinolaryngol 72: 1643-1650.

- Rajeshwary A, Rai S, Somayaji G, Pai V (2013) Bacteriology of symptomatic adenoids in children.N Am J Med Sci 5: 113-118.

- Wald ER (2011) Acute otitis media and acute bacterial sinusitis.Clin Infect Dis 52 Suppl 4: S277-283.

- Compalati E, Ridolo E, Passalacqua G, Braido F, Villa E, et al. (2010) The link between allergic rhinitis and asthma: the united airways disease Expert Review of Clinical Immunology 6: 413-442.

- Refaat MM, Ahmed TM, Ashour ZA, Atia MY (2008). Immunological role of nasal staphylococcus aureus carriage in patients with persistent allergic rhinitis. The Pan African Medical Journal 1: 3.

- Chalermwatanachai T, Velásquez LC, Bachert C (2015) The microbiome of the upper airways: focus on chronic rhinosinusitis.World Allergy Organ J 8: 3.

- Gelardi M, Iannuzzi L, Tafuri S, Passalacqua G, Quaranta N (2014) Allergic and non-allergic rhinitis: relationship with nasal polyposis, asthma and family history.ActaOtorhinolaryngolItal 34: 36-41.

- Staikuniene J, Vaitkus S, Japertiene LM, Ryskiene S (2008) Association of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps and asthma: clinical and radiological features, allergy and inflammation markers. Medicina (Kaunas) 44: 257-265.

- Ramakrishnan VR, Hauser LJ, Feazel LM, Ir D, Robertson CE, Frank DN. (2015) Sinus microbiota varies among chronic rhinosinusitis phenotypes and predicts surgical outcome. J Allergy ClinImmunol 136: 334-342.

- Ferguson BJ, Barnes L, Bernstein JM, Brown D, Clark CE 3rd, et al. (2000) Geographic variation in allergic fungal rhinosinusitis.OtolaryngolClin North Am 33: 441-449.

- Hidir Y, Tosun F, Saracli MA, Gunal A, Gulec M, et al. (2008) Rate of allergic fungal etiology of chronic rhinosinusitis in Turkish population.Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 265: 415-419.

- Braun H, Buzina W, Freudenschuss K, Beham A, Stammberger H (2003) 'Eosinophilic fungal rhinosinusitis': a common disorder in Europe?Laryngoscope 113: 264-269.

- Telmesani LM (2009) Prevalence of allergic fungal sinusitis among patients with nasal polyps.Ann Saudi Med 29: 212-214.

- Fair RJ, Tor Y (2014) Antibiotics and bacterial resistance in the 21st century.PerspectMedicinChem 6: 25-64.

Citation: Jangala M, Koralla RM, Manche SK, Akka J (2016) Microbial Prevalence and Antimicrobial Resistance in Children and Adolescents with Chronic Rhinosinusitis in South Indian Population. Otolaryngol (Sunnyvale) 6:248. DOI: 10.4172/2161-119X.1000248

Copyright: © 2016 Jangala M, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

ÌìÃÀ´«Ã½ Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 13436

- [From(publication date): 8-2016 - Jan 10, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 12652

- PDF downloads: 784